Behind the scenes of change

Theatre arts and criminal justice have become undeniable scene partners for victim-centered advocacy in the commonwealth June 24, 2025

Photos by Tom Fougerousse.

*Content Warning: This article discusses topics of assault and related trauma that may be sensitive for some readers

ACT I: Prologue

[A kind figure enters stage left on a bare, dim stage – then, a spotlight illuminates them]

NARRATOR: Empathy is a skill. (pause)

And thanks to an innovative partnership between the University of Louisville and justice organizations throughout Kentucky, law enforcement officers are learning it firsthand through the power of acting.

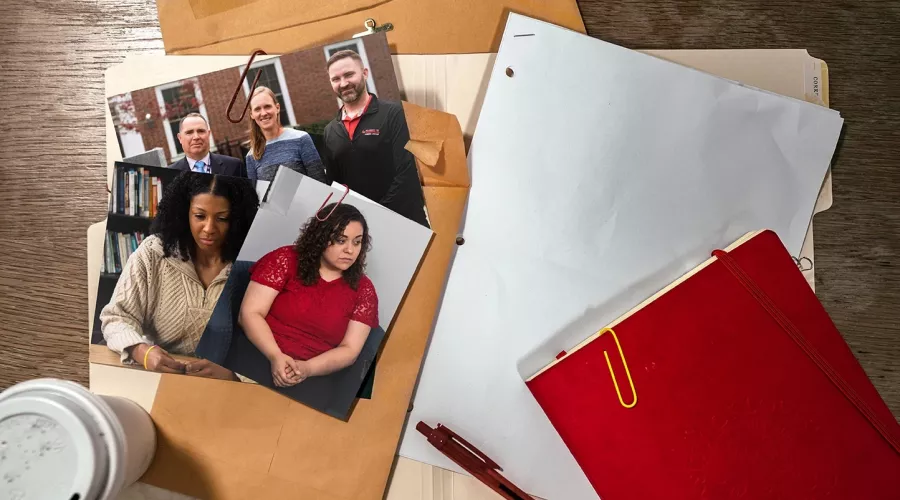

A collaboration between the theatre arts and criminal justice departments in the College of Arts and Sciences, along with community partners, positions UofL as a leader in victim-centered advocacy. By using actors to train officers in compassionate and sensitive interview techniques, UofL is helping reshape how victims of sexual assault are supported.

ACT I: Scene One

Ext. A backyard in Louisville, Kentucky

NARRATOR: It all started at a backyard barbecue in 2017 when Rachel Carter, associate professor of acting and voice; her partner Ted Carter, a simulation educator; and Bradley Campbell, associate professor of criminal justice and faculty member of the Southern Police Institute, began to talk about how simulation is used in the medical field.

They discussed how standardized patient training – actors portraying realistic medical scenarios – enhances medical students’ empathy and communication, allows them to practice classroom skills in a safe environment and leads to improved patient care. What if this approach was used with law enforcement? What if officers could train with actors to learn how to interact with trauma victims? Imagine the potential impact on real survivors, they pondered.

BRADLEY CAMPBELL: Research shows that if sexual assault survivors feel they were treated well and engaged in the process and given a voice, they are more likely to continue to engage. They are more likely to say they would report future crimes to the police, and they are more likely to tell other people to report those crimes to the police.

NARRATOR: Thus, over grilled foods and disposable dishes, a partnership between the theatre arts and criminal justice departments was created, leading to classroom training that emphasizes victim-centered and trauma-informed interview techniques.

ACT I: Scene Two

Int. An office in UofL’s Bigelow Hall

NARRATOR: The core idea behind the training is to equip law enforcement officers with both the knowledge and practical skills needed for victim-centered interviewing, all within a safe, controlled environment.

To bring this to life, Campbell partnered with Jim Root, an instructor at the Department of Criminal Justice Training under the Kentucky Justice & Public Safety Cabinet. Their collaboration involved months of research delving into trauma, neurobiology and the impact of questioning on the brain. The result is a comprehensive three-day training program designed to teach officers cognitive interviewing techniques, help them foster a deeper understanding of sexual assault survivors’ experiences and highlight the effects of trauma on memory. A crucial component of this training is the shift from closed-ended questions to open-ended, sensory-based questions. This approach acknowledges that trauma often disrupts a victim’s ability to recall events in chronological order.

JIM ROOT: In high school or when you were in journalism school, you are taught “Tell me your story from beginning to end.” Victims of trauma can’t do that. Their brain does not hold the information in a linear model. We explain in the training why that’s happening to people who have been victimized in trauma. And officers get it because we also experience critical incidents throughout our career.

NARRATOR: These investigative techniques are designed to minimize secondary trauma, which can occur when victims are forced to relive their experiences. Ultimately, Campbell emphasizes that acknowledging the trauma and treating survivors with empathy fosters a sense of collaboration between the survivor and the investigator.

BRADLEY CAMPBELL: The goal of the training is to ensure survivors are treated with respect and compassion, ultimately leaving the interview feeling supported and heard by the justice system.

ACT II: Scene One

Int. A welcoming space outfitted with comfortable chairs and a desk

NARRATOR: Traditional police training sometimes relies on fellow officers or instructors who have worked in policing for an extended period of time. That’s where Carter and the performers brought a crucial shift. Carter’s role lies in training standardized performers to authentically portray sexual assault survivors. This work, rooted in applied drama, creates a space for exploration where officers can practice skills and explore new approaches.

RACHEL CARTER: We created the survivor character with specific acting prompts detailing breath and vocal and physical choices so that performers could enter the survivor character for the simulation – but also created a ritual process for stepping out of that character.

NARRATOR: To ensure the wellbeing of the actors, they are debriefed after each simulated interview and at the end of each training day. Screening and clear communication about the nature of the role are also essential beforehand. Briana Linney ’18, ’23, whose social work experience has exposed her to numerous trauma survivors, brings a unique perspective to the role.

BRIANA LINNEY: I’ve been able to kind of mimic what trauma may look like for someone who (is not) in the moment of the trauma, but they have experienced it and depending on how you continue the conversation, they may shut down. They may get guarded. They feel judged. I keep that all in mind.

NARRATOR: The actors work from a highly realistic script, informed by actual police reports and input from sexual assault survivors, Kentucky Association of Sexual Assault Programs and other victim advocates. The commitment to authenticity is reflected in the feedback.

BRADLEY CAMPBELL: We have officers rank on a scale of 1 to 6 on how real your simulation felt and right now on a scale of 1 to 6, we are at a 5.8. The most important part is that not one person has said it is not a realistic simulation.

NARRATOR: The interview’s direction is dictated by the officer’s questions and actions. The actors are given “beats,” or shifts in the scene’s progression, based on the interaction. If an officer asks an interviewee to “start from the beginning,” the actor might portray confusion and avoid eye contact. Conversely, an officer who acknowledges the interviewee’s pain might see the actor’s breathing slow down and the actor begin to relax.

Aliyah Brutley ’21 views this type of acting gig as a powerful way to impact the community.

ALIYAH BRUTLEY: You can definitely see the difference in compassion. I can see them even hesitating or pausing before asking a question. I’ve had one man who recanted his statement in the middle of the training because he asked a “why” question which can be triggering for victims. In real time you are seeing them try to be respectful and mindful.

NARRATOR: The training’s success is rooted in collaboration with community partners. Victim advocates, such as the Army National Guard’s sexual assault prevention specialist Michelle Kuiper, played a crucial role in shaping the training’s direction and authenticity by connecting with other survivors.

MICHELLE KUIPER: It was important to bring to the table people who went through different types of crimes – all sexual assaults – but from different walks of life, whether that was through an LGBTQ+ lens, childhood trauma, someone who knew the person who assaulted them or someone who didn’t.

NARRATOR: Community partners, including Robyn Diez d’Aux, executive director of the Office of Victims Advocacy in the Kentucky Attorney General’s Office, also highlighted the broader impact of the collaboration.

ROBYN DIEZ D’AUX: Our law enforcement partners have told us just how valuable these trainings are. In many cases, they are the difference between solving cases and cases growing cold. Training officers through actor-portrayed simulation is the most accurate way to educate without re-victimizing survivors of crime. Providing law enforcement the opportunity to fine-tune their interview skills in the safety of an actor-portrayed simulation creates confident and informed officers who are better equipped to not only serve victims but also help prosecute.

ACT III: Final Scene

Int. A bare stage, Narrator in the spotlight’s pool

NARRATOR: The project initially received support through a grant from the U.S. Department of Justice’s National Institute of Justice agency. Campbell and Carter published their research in 2022.

The next pivotal step involves establishing the Center for Training, Research, and Innovative Simulation (TRAINS). Housed within the Southern Police Institute, TRAINS will leverage human-based simulation, virtual reality and other cutting-edge methods to enhance the effectiveness of criminal justice professionals. Michael Bassi, director of the Southern Police Institute, said the center will offer research and evaluation services to agencies at the local, state and national levels, while also fostering crucial cross-disciplinary collaboration.

(Bassi moves into spotlight)

MICHAEL BASSI: This (training) allows for a very, very realistic training that we really can’t recreate in any other way, and it allows us to increase our access to the industry that we serve. It’s also giving the students at UofL an exposure to all kinds of different and interesting types of education and training. It’s a great opportunity for everybody.

NARRATOR: TRAINS was made possible in part by a generous donation from Ed Pocock with the J. Allen Lamb & Edward S. Pocock III Foundation. Moving forward, the center will be self-sustaining through course registrations.

To prepare students for the specialized work conducted at TRAINS, the theatre arts department plans to offer a new course in acting for human-based training simulations. This initiative provides graduates with valuable, marketable skills and the potential to expand their career opportunities.

For Carter and Campbell, the mission remains clear: continue conducting research-driven work that positively impacts both survivors and law enforcement officers.

(Carter moves into the spotlight)

RACHEL CARTER: My hope is that this training changes the way law enforcement handles victim interviews, specifically interviews with sexual assault survivors. And that it encourages victims to trust law enforcement with their cases. I’ve had performers report in the debrief how touched they were when a law enforcement officer tells them they believe them. That should be the standard. I’m most proud when I hear an investigator say that this training will change or has changed how they approach victim interviews. Because that’s the goal.

[Lights dim. End.]

*If you or someone you know on campus has been impacted by interpersonal violence, assault or stalking, the UofL PEACC Center is an available advocacy resource for students, faculty and staff.

Audrie is a communications and marketing specialist in the Office of Communications & Marketing, where she highlights how UofL redefines student success. With a background in government communications, she brings a deep understanding of public service and the art of connecting with diverse audiences. Audrie holds a bachelor's degree in communications from Bellarmine University, with minors in history and political science.

UofL Magazine is the university's premier magazine for alumni and friends. To submit story ideas, provide feedback or contact the editor, please email editor@louisville.edu.