Changing tides

UofL researchers partner with rural community ravaged by floods to build a better future. October 15, 2025

Sirens pierced the black of early morning, echoing off the nearby mountains and rattling against the solid sheet of rain blanketing Valerie Horn’s home in Whitesburg, Kentucky.

The water rose through the night — higher and higher until her house was surrounded on all sides.

“We realized we had to get to high ground,” Horn said. “We knew it was extreme. We knew it was more than I’d ever seen. But still, we had no idea the magnitude of what was happening out in the rest of the county.”

The floods came in summer of 2022. When all was said and done, they had devastated parts of Cowan County — some of the state’s most rural communities — resulting in dozens of deaths and many reported missing. Others found their homes completely destroyed or lifted off their foundations and carried clear to downtown. Horn was one of the lucky ones. And now, she hopes to be part of the solution.

Thanks to a $4 million grant from the National Science Foundation’s Focused EPSCoR Collaborations (NSF FEC) program, she and other community members are working with a multi-disciplinary research team from UofL and other universities across Kentucky and West Virginia. Their goal is to study flooding across the Appalachian region and protect people by mitigating the impact of future floods.

“This place was just ravaged,” said Mary Brydon-Miller, a professor in the College of Education and Human Development and a lead on the community engagement component.

People lost their homes or had to be rescued off their roofs. But it’s also an extraordinarily resilient community, and it’s only by working with them that we can find solutions that will actually work.

- Mary Brydon-Miller

Meeting of minds

The team gathers in the octagonal Cowan County Community center — blink and you’ll miss it off the windy mountain road in the heart of coal country. It’s a place for birthday parties, wedding receptions and beginners’ yoga classes.

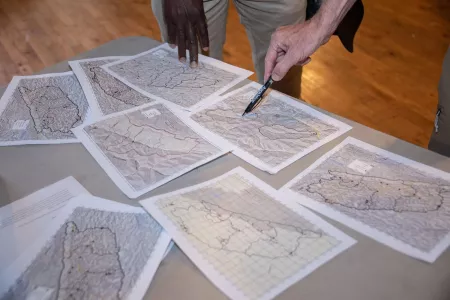

But today, researchers and community members gather around maps of watersheds and discuss their first steps in solving a problem that just a few years ago, took dozens of lives.

“Those floods came extremely quickly,” said principal investigator Tyler Mahoney, assistant professor at the UofL J.B. Speed School of Engineering. “We need to understand what causes flash floods in these small Appalachian catchments and find ways to enhance warning times in the future.”

Mahoney and his team will work to understand those causes and how they might have changed over time, perhaps with land use or climate change. They’ll plant sensors throughout the watershed to gauge rainfall and monitor the water’s ebb and flow. The data, he hopes, will help the researchers better predict how and when flash flooding events will happen and give people more notice to evacuate.

Notice is critical. Without notice, Horn might not have made it to higher ground — the community kitchen at the highest point in Whitesburg, where she spent the night of the flood dishing out hot meals to her displaced neighbors arriving on boats and jet skis.

How do we move from reactionary to more planning? We know there’s a rush of adrenaline that comes in crisis. We need to move toward being prepared.

— Valerie Horn

Working together

While Mahoney works to understand the physical and natural causes of flooding, another team led by Brydon-Miller will work with the community to better understand the human element — their response, recovery and possible solutions to prevent future disasters.

It’s a method called participatory action research, where researchers draw insights and ideas from the people who know the problem best. For example, community members have helped identify potential flood points and connect with landowners to place sensors.

“That kind of local knowledge is just invaluable,” Brydon-Miller said. “I think too often, researchers come in and they plunk something down and they say ‘here’s the solution to your problem’ without ever asking ‘what is the problem from your perspective?’ ”

That, she said, can result in solutions that are half-baked, don’t actually address the problem or aren’t realistic. Over the four-year project period, the researchers will hold workshops, brainstorming sessions and interviews with community members to better understand the floods’ impact. The goal is to find solutions that aren’t just theoretical, but practical and that fit easily into locals’ day-to-day lives.

“I feel that the whole research team for this project understands that,” she said, “and so I feel very confident that by working with the community, the solutions we co-develop will be ones that can actually be used.”

Thousand-year flood

That’s especially important because, by all accounts, the flood of 2022 won’t be the last one. In its aftermath, people referred to it as a ‘1,000-year event.’

“Well it’s not a 1,000-year event,” said Brydon-Miller, who also studies climate change education. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), global adverse weather events are increasing in frequency and intensity. That leaves communities like Whitesburg vulnerable.

“If we could just find a strategy — not just the technology, but a strategy — for working in communities and helping them understand what can be done and how they can be more resilient in the face of flood events, that’s going to be important knowledge,” she said. “I see the potential impact for what we’re doing here as being really, really important.”

The goal is to develop a wholistic strategy that could be applied not only in Whitesburg, but in communities around the world, to keep people safe. That strategy likely includes not only sensors, mapping and warnings, but education and a fuller understanding of what it takes for a community to recover from an adverse weather event and grow stronger.

“Adverse weather events like this happen everywhere and they’re very complex,” said Stephanie Grace Prost, an associate professor with the UofL Kent School of Social Work and Family Science and co-lead on the community engagement portion of the project. “They involve not only the environmental facets but also human responses such as trauma and resilience.”

In Whitesburg, the researchers are working to develop those tools — to understand the trauma and engage people in finding solutions to problems that affect them most. It’s an ongoing partnership that both sides have fully embraced.

“I feel like few things are isolated,” Horn said. “Hard things don’t get solved when we silo them, or when we don’t see the full picture or the full system. One of the things that matters most to people in Eastern Kentucky is to be recognized and to be seen. And so, when you have an institution like UofL that’s recognizing a community and valuing them, as Mary and Tyler do, and they come to us as partners … it’s the pinnacle of what you want to be doing and should be doing.”

Baylee Pulliam leads research marketing and communications at UofL, building on her experience as an award-winning business, technology, health care and startups reporter. She is a proud product of the UofL College of Arts and Sciences, where she earned her undergraduate degree in English. She also holds an MBA, a Master of Arts in Organizational Leadership and is pursuing a Ph.D. in the latter with a focus on corporate innovation.

Related News