This land is your land?

DNA research digs into the origins of far-flung ancestral homelands – and how our ancestors actually got there June 24, 2025

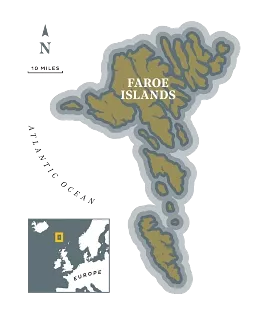

The Faroe Islands. Photo by Mark Zimmer.

Where did your ancestors come from? What impact did they have on who you are?

Since the early 2000s, millions of people have taken advantage of at-home DNA testing available through companies like AncestryDNA to learn about their family histories and gain clues to their ancestors’ origins.

Associate Professor of Anthropology Christopher Tillquist uses the same types of genetic data to research human migration across centuries and millennia. Tillquist uses living peoples’ genes to verify or refute the misty origin stories of an area’s founders. He scours DNA to dig deep into time to learn about an area’s founders, as well as the impact of historical events on an area’s population.

As an evolutionary anthropologist, Tillquist uses population genetics and evolutionary theory to document how history can be traced through people's genes.

“I'm essentially a genetic detective," Tillquist said. "I use DNA from living people to test the stories we've told ourselves about who founded different populations and how historical events shaped the genetic makeup of regions."

While he studies populations around the globe, his recent research aligns with his interest in his own family history.

“My ancestors on both sides come from Sweden and Norway,” Tillquist said. “I've always been fascinated by how my Scandinavian background shapes my worldview and social interactions. As an anthropologist, I'm constantly observing these cultural influences, and they've definitely inspired my research direction.”

His most recent published study examines the current population of the Faroe Islands, a remote island group in the North Atlantic west of Norway said to have been settled by a Viking chief in the 9th or 10th century – but the genetic evidence tells a more nuanced story.

Following DNA’s breadcrumbs

To document the Faroes founders through modern DNA research, Tillquist used data from living residents’ Y chromosomes. Since these chromosomes pass exclusively from fathers to sons, they provide an unbroken genetic line through male ancestry.

Y chromosomes carry genetic patterns than can be traced to deep origins in various parts of the world as well as evidence of more recent mutations. Like breadcrumbs left to retrace your footsteps, these genetic patterns give Tillquist clues to the origins of people who founded a population and the influence of others who passed through the place over time.

Legend and geographic proximity would indicate that Vikings settled both the Faroe Islands and Iceland. Because of their remote and relatively isolated locations, the island countries’ founding fathers’ genes would be expected to be preserved in the present inhabitants, giving Tillquist a clearer picture of their genetic origins than a more well-visited location.

Tillquist and his colleagues – former graduate student Allison E. Mann ’09, ’12, now assistant professor at the University of Wyoming, and a Faroese researcher, Eyðfinn Magnussen, associate professor at the University of the Faroe Islands – analyzed de-identified Y chromosome data sampled from males living in the Faroes and Iceland. They compared two categories of genetic markers in those samples with data from residents of Denmark, Sweden, Norway and Ireland to tease out the origins of the founding fathers.

The two types of markers used were haplotypes and haplogroups. Haplogroups are classifications based on specific mutations known as single nucleotide polymorphisms that can reveal a general geographic origin, like the Middle East, Africa or northern Europe from deep in the past. DNA researchers have classified roughly 20 major haplogroups for the world’s population by letter, with numbers added to distinguish subgroups.

Haplotypes, another category of genetic markers, are short tandem repeats in specific locations on the DNA, called microsatellites. Similar patterns in microsatellites are classified into haplotypes, which reveal more recent and more specific heritage than haplogroups.

While most researchers use microsatellites to study genetic variation in populations a few hundred years old, such as the Faroes settlement, Tillquist took a slightly different approach. He looked at the microsatellites in the context of their haplogroup, giving a more accurate picture of the population’s diversity than microsatellites alone.

“So, we looked at it by haplogroup first, then from there you can have a better idea of how diverse things really are,” Tillquist said. “Even if you have a relatively diverse looking population, if you split it out by haplogroup then you get a better fix of what is the true relative variability of the microsatellites.”

We're all walking historical documents. Our DNA tells stories our written records never captured – it's just a matter of learning how to read them.

Not surprisingly, the men’s genes indicated both the Faroe Islands and Iceland indeed were founded largely by people from Scandinavia. The surprising aspect was that the populations originated from different founding groups, with Faroe Islands founders showing less relation to Ireland and more to Norway than did Iceland, although both areas’ founding fathers came mostly from Denmark and Norway.

Tillquist is investigating other island populations as well. His next paper will look at diversity in mitochondrial DNA on the Shetland Islands, off the northern coast of Scotland. The mitochondrial genome is passed on exclusively through maternal lines.

Evolving the evolution simulation

Ultimately, Tillquist hopes to use knowledge gained from the less-complex island populations to develop simulation techniques that will allow him to genetically trace the peopling of Europe.

“My long-term interest is to figure out Europe. There have been thousands of migrations in Europe. Which ones have made lasting impacts? The population structure seems very stable now, but I want to know how it got that way,” Tillquist said.

“Are we seeing genetic patterns established 15,000 years ago or 1,000 years ago? Did the Mongol invasions permanently alter European genomes or were they genetically insignificant? The Viking expansions clearly left their mark, but what about the impact of the Goths, who ultimately played roles in the history of the Roman empire? I’m hopeful that we can detect this type of historical movement in today’s DNA.”

Tillquist plans to use an innovative approach, combining forward-looking and backward-looking simulation techniques to understand how evolutionary processes and historical events shaped a population’s genetics.

“In the forward model, we create a founding population and simulate various historical events through generations,” he said. “Then we use backward methods, sampling today's populations and applying computational models to work back through time to assess the fit of the sampled data to the models. By comparing both approaches, we can triangulate what really happened with much greater confidence."

This methodology has the potential to transform the understanding of European genetic history and rewrite aspects of the historical narrative.

Whether applied to the population of a continent or an individual, Tillquist’s research demonstrates how our DNA carries the stories of countless ancestors and historical events that shaped our genetic identity.

“We’re all walking historical documents,” Tillquist said. “Our DNA tells stories our written records never captured – it’s just a matter of learning how to read them.”

Explore more stories from the spring/summer 2025 issue of UofL Magazine

Betty Coffman is a communications coordinator focused on research and innovation at UofL. A UofL alumna and Louisville native, she served as a writer and editor for local and national publications and as an account services coordinator and copywriter for marketing and design firms prior to joining UofL’s Office of Communications and Marketing.

UofL Magazine is the university's premier magazine for alumni and friends. To submit story ideas, provide feedback or contact the editor, please email editor@louisville.edu.