Philosophy of the blasé

UofL Research reframes boredom as an opportunity to build deeper meaning in life’s experiences. October 14, 2025

No one likes being bored and most people will do anything to avoid it. But what if that monotonous, dull, blasé boredom could be … a good thing?

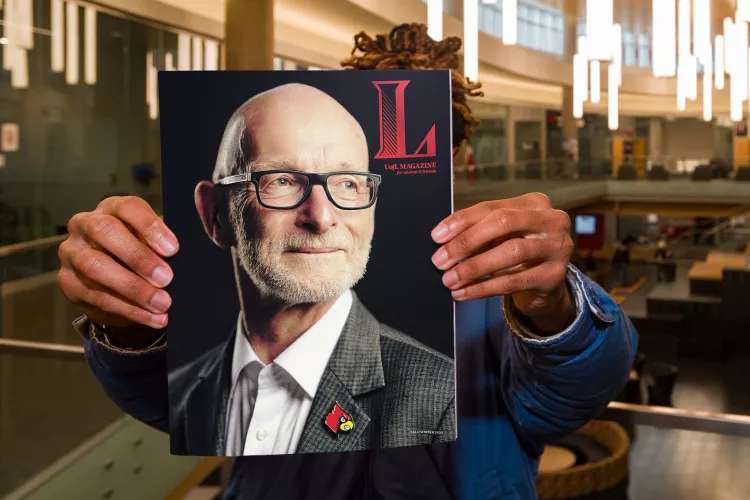

Research from Andreas Elpidorou, director of liberal studies and professor of philosophy, shows boredom might actually be a catalyst for good in our lives, if we are willing to listen, and that it can drive us to pursue bigger and better things — say, a new job or hobby.

“Boredom motivates us to act because it doesn’t feel good and because it involves a desire for doing something else, to seek alternative occupations and tasks,” he said.

“Thus, boredom stands as a catalyst for action. This is all good news because we’re burning for change when we’re bored. And boredom itself is there to help us.”

There’s a broad scientific consensus that boredom is an emotional state of dissatisfaction with our current situation, one that involves a powerful desire for change. But desire is nothing without action. If we act, Elpidorou says, boredom becomes a functional tool — it regulates cognitive engagement, driving humans to make the changes they need to seek and achieve more meaning in life.

“There is a whole gamut of possible responses to boredom, like taking up a hobby or people writing novels because they’re bored; or even consider someone like former President George W. Bush who said that he picked up painting because he was bored.”

Another reason boredom might be seen as a “bad” thing may stem from the belief that it indicates a lack of productivity. But Elpidorou believes that by reframing this view allows human beings to become more mindful about boredom by recognizing it, listening to it and reflecting on why a specific situation may be “boring.”

Being more mindful can help people to recognize when boredom arises, and to develop emotional literacy about their own personal experiences. Not every moment of boredom is going to be significant and tell us something about ourselves and our lives — but sometimes it will.

— Andreas Elpidorou

AI boredom

Elpidorou’s research also shows that boredom might not be the purely human experience we think it is.

Through his functional view of boredom, he argues that it’s not tied to specific physiological features of the brain, but is instead a functional mechanism that could be present in various types of brains, including animals and even possibly artificial intelligence (AI) agents. Evidence shows that animals engage in behaviors beyond survival needs, indicating cognitive engagement and supporting the idea that they can certainly experience boredom, but perhaps not in an identical way that humans do. Thus, based on the functional definition, it is natural to conclude that animals experience boredom.

He also said that certain autonomous AI systems could experience boredom in the future. After all, if boredom is understood functionally, then any system would be capable of experiencing boredom as long as it can implement the function associated with boredom. Indeed, some researchers are working to implement boredom-like mechanisms in machines right now. The goal is to prevent AI from getting stuck in repetitive loops or wasting resources on unnecessary tasks.

Zen and the art of boredom

Elpidorou said it is important to employ strategies to embrace boredom, and to make the most out of its possible positive impacts in our lives. The first is to reframe situations we may find boring but cannot avoid.

“When we come to see a situation as meaningful, it’s less likely that we’re going to experience that situation as boring,” he said.

The second is to engage in different activities that bring us deeper meaning or that are personally significant to us, including hobbies like writing, painting or crafting, cultivating relationships by calling a friend or inviting members of the family over to visit, or physical activity like taking a walk or playing a sport.

“That work often needs to happen before we’re bored or in anticipation of being bored, because in the moment of boredom, it’s really hard to think about what to do and it’s even harder to actually do it.”

The effectiveness of boredom all depends on your response to it.

And so, boredom is neither a negative or a positive, rather, a mechanism we can use to our advantage to find and cultivate deeper meaning in our interactions, relationships, work and in our daily activities.

Stephanie Godward, communications and marketing director, College of Arts & Sciences

Related News